In the News

As the social care sector now deals with the requirement for its workers to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, fears continue to grow for both users and providers regarding what this will mean for the provision of care.

The state of care

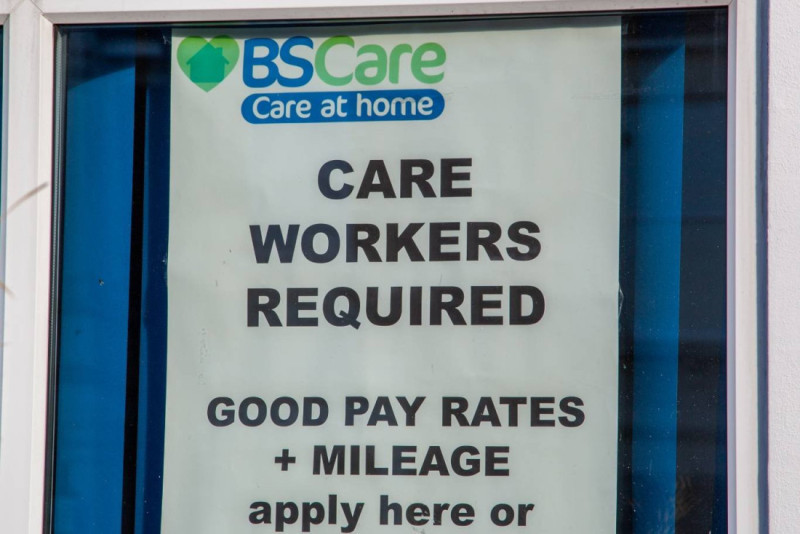

At the end of October, the CQC released its ‘State of Care 2021’ report, assessing both health and social care in England, trends, and areas of improvement. For social care, the report made for grim reading. The pandemic has increased the pressure on adult social care significantly, reducing financial capacity by over 10 per cent and, in particular, leading to difficulties recruiting and retraining staff, leading to worries of a “tsunami of unmet need”. This is underlined by the news that the numbers on care waiting lists have doubled in just one year.

The issue of staff is seen by many to be the key issue facing providers. Some care home managers, around 63.5 per cent, fear they may have to close their homes due to shortages, which will only be exacerbated by mandatory COVID jabs. Even if they do not fear closure, providers are worried they may have to hand back care contracts they can no longer fulfil.

Care workers have been leaving the industry in their thousands. Statistics from Skills for Care show that at any one time this year there have been around 105,000 vacancies in the sector, with an average turnover rate of 28.5 per cent.

What measures have been proposed?

In the Chancellor’s recent budget and spending review, he committed to a three per cent increase in the spending power of councils and £4.8 billion of new grant funding for social care for councils. However, reaction to this has not been favourable.

Nigel Edwards, chief executive of the Nuffield Trust, said following the commitment was “not be enough to truly overhaul a broken system that leaves hundreds of thousands without the care they should get”. This was echoed by vice-president of the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) Sarah McClinton, who said that adult social care is facing “a perfect storm” and it was “disappointing that the Chancellor failed to recognise the crisis in social care that is already upon us.”

As well as the lack of funding for service provision, worries were also expressed around the costs of the rise in the national living wage (NLW) to £9.50 an hour. David Brindle, chair of care charity Ambient Support, suggests that there would need to be a four per cent increase in the fees paid to providers by councils and the NHS to meet the additional costs.

Labour leader Keir Starmer has backed a campaign to help lift the strain on the sector and its “exhausted and demoralised” workers by, among other measures, adding care to the skills shortage lists so that migrant staff can fill vacancies. This is backed by Care England, with its chief executive Martin Green stating “without immediate help, as given to the NHS, the social care sector will crumple”.

Interview

For the November edition of Cura Insight, we spoke to Vic Rayner, Chief Executive of the National Care Forum. She argues the skills shortage facing the sector is undoubtedly its biggest challenge, and that without prompt action care delivery will be at even greater risk.

What, in your view, are the greatest challenges affecting the adult social care services sector at the moment?

I think the biggest thing right now is the workforce; people leaving and the challenge of recruiting new staff to come and work within the sector. I think there are a lot of other things that are around trying to understand how, when the rest of the country is going back to something approaching normal, how do care organisations continue to navigate within a quite strongly controlled environment around protection, prevention, control and testing and vaccination obviously as well?

I think there's something about understanding what the model of care will look like going forward. So people trying to work through that as well. And I mean I think there are ongoing problems for organisations in terms of funding which is exacerbated by trying to think about how to pay people appropriate levels for their skills and expertise.

Is the Chancellor’s commitment of £4.8 billion in new grant funding for local councils, on top of the new social care levy, enough in your view to stave off the crisis that the sector is facing at the moment?

No. The extra £4.8 billion for councils is not ring fenced for social care. Local authorities have wide-ranging responsibilities across all sorts of areas that need funding with that money

We've had additional funding in the last year through infection control funding, recruitment and retention funding and testing funds, but we don’t anticipate a repeat of this funding.

Along with the shortfall there, we also have to deal with:

Anticipated inflation of around 5 per cent

Energy bills in home care

Increases in fuel costs for travel

Wage inflation - if people's costs go up 5 per cent, then they're going to need to see their salaries compensating for that.

In April 2022, I don't think the care sector will see any of the money from the proposed health and social care levy. It may see some training and development funding, but I think any other monies that come out of that levy will end up being absorbed into the local authority system.

How is the sector addressing the current labour shortages in the short term?

Currently, three coping strategies are on show. The first is handing back care contracts or not taking new admissions. The second is asking staff to work large amounts of overtime, and the third is the increasing use of agency staff, whose exponential cost increases are completely unsustainable for providers.

The Government has to take some action because individual providers can't carry on. They can't raise prices, and they can’t raise staff salaries because they don't have any additional money coming in.

Without the further abilities to raise self-funded fees (owing to Competition and Market Authority rules) or get more money from local authorities due to inflexibility of contracts, the only real way to address some of this is three things we've been asking for:

Government pays all care workers a retention bonus.

Government announces an increase in all care staff's pay

Reinstating ‘care workers’ on the shortage occupation list, so that we can look to hire fantastic, talented staff from all over the globe.

What will happen if the sector’s skills shortage is not resolved?

I think what will happen is that we will be finding that organisations have had to take some very drastic steps to protect the staff group that they have.

People in communities will be unable to access the care that they need, putting pressure on unpaid carers and family members and people themselves.

I don't think the care sector will see any of the money from the proposed health and social care levy

Alternatively, you'll have people in hospital who can't get back into their own home or into a care home. So much evidence shows if you are medically fit to be discharged from hospital then staying in hospital is the worst possible place for you to be. I think we're seeing that already and we will see more of that. In that context, you've got people with a statutory right to care which is not able to be delivered.

With longevity increasing and demands for social care services forecast to grow over the coming years, how can this increased demand be met in the long term?

Looking ahead, we have to put in place a professionalisation agenda that means people are paid properly for their skills and that establishes career pathways with fixed points of salary. Without that we are going to be yo-yoing between feast and famine as the wider job market changes.

The second thing is we absolutely need to get our investment right in digital solutions.

Recent data says that we're going to need an additional half a million workers. But greater longevity means fewer working age people, not just more people needing care.

A shrunken workforce reduces care's ability to attract those half a million extra workers. We desperately need digital solutions to meet people’s care needs, be that robots, be that more intuitive care planning systems which allow you to choose when you need services. But we cannot just invest; we need a proper digital strategy that says what we think care will look like and how people will experience it and how that will be underpinned by a digital offering. Otherwise, we will fail fast.

Opinion

For the November edition of Cura Insight, Adam Purnell, Director of Social Care at the Institute for Health and Social Care Management, argues that ‘change’ should be the buzzword for the sector when it comes to solving the current crisis, not ‘fix’.

Revitalizing the Social Care Workforce in the Face of Growing Demands

The staffing crisis in social care is not something that is new, but it is something that is progressively more concerning, made worse by the policy mandating vaccination in care homes and soon the wider care sector. It’s estimated that there were around 110,000 vacancies in social care prior to the mandate, with tens of thousands added to this post mandate and a projection of a requirement of another 500,000 more staff by 2035.

With so few people entering the sector, how do we solve the problem?

One could argue it’s about money. We should be paying our social care workforce better wages as the social care sector takes on more responsibility. Care workers are seeing their workloads increase and become more professional - their wages should reflect this. Personally, I believe in an elevated wage of £12.50 upwards, but maybe we should start small and aim for parity between social care workers and NHS workers, who are paid on average £7500 more as discovered in the ‘unfair to care’ report.

Too much focus is put on ‘fixing’ the sector when we should be suggesting changing it instead

It’s not just about money though. Career image has been an afterthought for many years in social care, with many unaware of the variety of career choices, be it chef, activity coordinator, manager, social care nurse. Maybe a skills register or a professional database would be one step towards cementing a care as a true career choice?

It also comes down to satisfaction. The pandemic has taken its toll both physically and mentally on our social care workforce, with an increase of burnout, stress, and even PTSD plaguing the workforce. We need to normalise saying “thank you” and being grateful for the work our care teams do. At the Institute of Health and Social Care Management, we have recently partnered with TAP – Thank and Praise, which is a free to use thanks and gratitude platform aiming to help the sector make thanking easier.

Too much focus is put on ‘fixing’ the sector when we should be suggesting changing it instead. Working hours need to adapt a more flexible approach align with the busy lives of people. Too often we see in care homes rigid shift structure that ostracise working parents or others with equal time commitments.

The conversation of recruitment and retention is a lengthy one that is also heavily reliant on quality training, wellbeing support, values-based recruitment amongst a raft of other things.

The ‘fix’ won’t occur by just sorting one of these issues, but by working in collaboration with health and the government and by engaging with providers to create and adapt the sector.